Apollo Lunar Module

| Apollo Lunar Module | ||

|---|---|---|

Apollo 16 LM Orion on the lunar surface |

||

| Description | ||

| Role: | manned lunar landing and takeoff | |

| Crew: | 2; CDR, LM Pilot | |

| Dimensions | ||

| Height: | 17.9 feet (5.5 m) | |

| Width: | 14.0 feet (4.3 m) | |

| Depth: | 13.3 feet (4.1 m) | |

| Landing gear span: | 29.75 feet (9.07 m) | |

| Cockpit volume: | 235 cubic feet (6.7 m3) | |

| Masses | ||

| Ascent stage: | 10,024 pounds (4,547 kg) | |

| Descent stage: | 22,375 pounds (10,149 kg) | |

| Total: | 32,399 pounds (14,696 kg) | |

| Rocket engines | ||

| LM RCS (UDMH/N2O4) x 16: | 100 pounds-force (440 N) | |

| Ascent Propulsion System (Aerozine 50/N2O4): |

3,500 pounds-force (16,000 N) | |

| Descent Propulsion System (Aerozine 50/N2O4): |

9,982 pounds-force (44,400 N) at full throttle; throttle range of 1,050 pounds-force (4,700 N) to 6,800 pounds-force (30,000 N) | |

| Performance | ||

| Endurance: | 3 days plus (75 hours) | |

| Apolune: | 100 miles (160 km) | |

| Perilune: | surface | |

| Spacecraft delta v: | 15,390 feet per second (4,690 m/s) | |

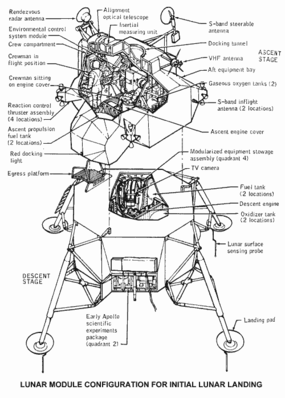

| Apollo LM diagram | ||

Apollo LM diagram (NASA) |

||

| Grumman Apollo LM | ||

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) was the lander portion of the Apollo spacecraft built for the US Apollo program by Grumman to carry a crew of two from lunar orbit to the surface and back. Six such craft successfully landed on the Moon between 1969–1972.

The LM, consisting of an Ascent stage and Descent stage, was ferried to lunar orbit by its companion Command/Service Module, a separate spacecraft approximately twice as massive, which took the astronauts home to Earth. After completing its mission, the LM was discarded. In one sense it was the world's first true spacecraft in that it was capable of operation only in outer space, structurally and aerodynamically incapable of flight through the Earth's atmosphere.

Though initially unpopular and plagued with several delays in its development, the LM eventually became the most reliable component of the Apollo/Saturn system, the only one never to suffer any failure that significantly impacted a mission,[1] and in at least one instance (LM-7 Aquarius) greatly exceeded its design requirements.

Contents |

Operational profile

At launch, the Lunar Module sat directly beneath the Command/Service Module (CSM) with legs folded, inside the Spacecraft-to-LM Adapter (SLA) attached to the S-IVB third stage of the Saturn V rocket. There it remained through earth parking orbit and the Trans Lunar Injection (TLI) rocket burn to send the craft toward the Moon.

Soon after TLI, the SLA opened and the CSM separated, turned around, came back to dock with the Lunar Module, and extracted it from the S-IVB. During the flight to the Moon, the docking hatches were opened and the LM Pilot entered the LM to temporarily power up and test its systems (except for propulsion). Throughout the flight, he performed the role of an engineering officer, responsible for monitoring the systems of both spacecraft.

After achieving a lunar parking orbit, the Commander and LM Pilot entered and powered up the LM, replaced the hatches and docking equipment, unfolded and locked its landing legs, and separated from the CSM, flying independently. The Commander operated the flight controls and engine throttle, while the Lunar Module Pilot operated other spacecraft systems and kept the Commander informed on systems status and navigational information. After inspection of the landing gear by the Command Module Pilot, the LM was withdrawn to a safe distance, then the descent engine was pointed forward into the direction of travel to perform the 30 second Descent Orbit Insertion burn to reduce speed and drop the LM's perilune to within approximately 50,000 feet (15 km) of the surface[2], about 260 nautical miles (480 km) uprange of the landing site.

At this point, the engine was started again for Powered Descent Initiation. During this time the crew flew on their backs, depending on the computer to slow the craft's forward and vertical velocity to near zero. Control was exercised with a combination of engine throttling and attitude thrusters, guided by the computer with the aid of landing radar. During the braking phase altitude decreased to approximately 10,000 feet (3.0 km), then the final approach phase went to approximately 700 feet (210 m).During final approach, the vehicle pitched over to a near-vertical position, allowing the crew to look forward and down to see the lunar surface for the first time.[3]

Finally the landing phase began, approximately 2,000 feet (0.61 km) uprange of the targeted landing site. At this point manual control was enabled for the Commander, and enough fuel reserve was allocated to allow approximately two minutes of hover time to survey where the computer was taking the craft and make any necessary corrections. (If necessary, landing could have been aborted at almost any time by jettisoning the descent stage and firing the ascent engine to climb back into orbit for an emergency return to the CSM.) Finally, three-foot-long probes extending from three footpads of the lander touched the surface, activating the contact indicator light which signaled time for descent engine cutoff, allowing the LM to settle on the surface.

When ready to leave the Moon, the LM would separate the descent stage and fire the ascent engine to climb back into orbit, using the descent stage as a launch platform. After a few course correction burns, the LM would rendezvous with the CSM and dock for transfer of the crew and rock samples. Having completed its job, the LM was separated and sent into solar orbit or to crash into the Moon.

History

The Lunar Module (originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module or LEM, a pronounceable acronym) was designed after NASA chose to reach the Moon via Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) instead of the direct ascent or Earth Orbit Rendezvous (EOR) methods. Both direct ascent and EOR would have involved landing a much heavier, complete Apollo spacecraft on the Moon. Once the decision had been made to proceed using LOR, it became necessary to produce a separate craft capable of reaching the lunar surface and ascending back to lunar orbit.

The LEM was built by Grumman Aircraft Engineering and was chiefly designed by the American aerospace engineer, Tom Kelly.[4] Grumman had begun lunar orbit rendezvous studies in late 1950s and again in 1962. In July 1962, eleven firms were invited to submit proposals for the LM. Nine did so in September, and Grumman was awarded the contract that same month. The contract cost was expected to be around $350 million. There were initially four major subcontractors—Bell Aerosystems (ascent engine), Hamilton Standard (environmental control systems), Marquardt (reaction control system) and Rocketdyne (descent engine).

The Primary Guidance, Navigation and Control System (PGNCS) was developed by the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory; the Apollo Guidance Computer was manufactured by Raytheon.[5] A backup navigation tool, the Abort Guidance System (AGS), was developed by TRW.

Over the course of its development, the name was officially changed to Lunar Module (LM), eliminating the word "excursion". This was because NASA was pushing to get funding for some kind of powered lunar surface mobility and they wanted to make it clear that such "excursions" were beyond the capabilities of the lunar lander itself. (This new excursion capability was eventually realized with the Lunar Rover.) After the name change from "LEM" to "LM", the pronunciation of the abbreviation did not change, as the habit became ingrained among engineers, the astronauts, and the media to universally pronounce "LM" as "lem" which is easier than saying the letters individually.

Design phase

Early configurations of the LEM included a second, forward docking port; initially, it was believed the LEM crew would take an active role in docking with the CSM. The early design also included large curved windows and seats for the astronauts, like a helicopter cockpit.

As the program continued, there were numerous redesigns to save weight (including "Operation Scrape"), improve safety, and fix problems. The final design eliminated the glass cockpit, seats and the forward docking port (the astronauts stood while flying the LM, and the Command Pilot could see the approaching CSM through a small overhead window while the active role was performed by the Command Module Pilot.) This allowed the design of smaller windows and a lighter structure, resulting in significant weight savings. Egress while wearing Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) spacesuits was also made easier by a simpler-opening forward hatch.

A configuration freeze did not start until April 1963, when the ascent and descent engine designs were decided. In addition to Rocketdyne, a parallel program for the descent engine was ordered from Space Technology Laboratories in July 1963, and by January 1965 the Rocketdyne contract was canceled.

Power was initially to be produced by fuel cells built by Pratt and Whitney similar to the CSM, but in March 1965 these were discarded in favor of an all-battery design. [6]

The initial design had three landing legs. As any particular leg would have to carry the weight of the vehicle if it lands at any significant angle, three legs was the lightest configuration. However, it would be the least stable if one of the legs were damaged during landing. The next landing gear design iteration had five legs and was the most stable configuration for landing on an unknown terrain. That configuration, however, was too heavy and the designers compromised on four landing legs. [7]

Astronaut training

To allow astronauts to learn lunar landing techniques, NASA contracted Bell Aerosystems in 1964 to build the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV), which used a gimbal-mounted vertical jet engine to counter 5/6 of its weight to simulate the Moon's gravity, in addition to its own hydrogen peroxide thrusters to simulate the LM's descent engine and attitude control. Successful testing of two LLRV prototypes at the Dryden Flight Research Center led in 1966 to three production Lunar Landing Training Vehicles (LLTV) which along with the LLRV's were used to train the astronauts at the Houston Manned Spacecraft Center. This aircraft actually proved fairly dangerous to fly, as three of the five were destroyed in crashes. It was equipped with a rocket-powered ejection seat, so in each case the pilot survived, including the first man to walk on the Moon, Neil Armstrong.[8]

Development flights

The first unmanned LM flight was planned for April 1967, but because of development delays did not occur until January 22, 1968 when the Apollo 5 flight launched the LM-1 atop a Saturn IB for propulsion systems testing in low Earth orbit. A second unmanned test flight of LM-2 was originally planned, but canceled as unnecessary.

The first manned LM flight was also delayed, planned for Apollo 8 in December 1968 but not occurring until Apollo 9 using LM-3 on March 3, 1969 to test the LM's systems, separation and docking in low Earth orbit. Apollo 9 had been planned as a second manned, higher Earth orbit practice flight, but this was cancelled to keep the program timeline on track.

Apollo 10, launched on May 18, 1969, was a "dress rehearsal" for the lunar landing, practicing all phases of the mission except powered descent initiation through takeoff. The LM descended to 47,400 feet (14.4 km) above the lunar surface, then jettisoned the descent stage and used its ascent engine to return to the CSM.[9]

Production flights

The first manned lunar landing occurred on July 20, 1969 with the Apollo 11 LM Eagle, achieving President John F. Kennedy's goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth." Eagle safely returned its crew members to the Command Module, which safely splashed down four days later.

This was followed by precision landings on Apollo 12 (Intrepid) and Apollo 14 (Antares) with the aid of upgraded computers and navigational techniques.

In April 1970, the Apollo 13 Lunar Module Aquarius played an unexpected role in saving the lives of the three astronauts after an oxygen tank in the Service Module ruptured, disabling the CSM. Aquarius served as a "lifeboat" for the astronauts during their return to Earth. Its descent stage engine was used to replace the crippled CSM Service Propulsion System engine, and its batteries supplied power for the trip home and recharged the Command Module's batteries critical for re-entry. The astronauts splashed down safely on April 17, 1970. The LM's systems, designed to support two astronauts for 45 hours, actually stretched to support three astronauts for 90 hours.

Extended J Class Missions

The Extended Lunar Modules (ELM) used on the final three "J-class missions", Apollo 15, 16 and 17, were significantly upgraded to allow for greater landing payload weights and longer lunar surface stay times. The descent engine power was improved by the addition of a 10-inch (250 mm) extension to the engine bell, and the descent fuel tanks were increased in size. A waste storage tank was added to the descent stage, with plumbing from the ascent stage. These upgrades allowed stay times of up to 75 hours on the Moon.

The Lunar Roving Vehicle was carried, stowed on Quadrant 1 of the ELM descent stage and deployed by astronauts after landing. This allowed them to explore large areas and return a greater variety of lunar samples.

Hover times and landing weights were also maximized by using the Service Module engine to perform the initial Descent Orbit Insertion burn before the LM separated from the CSM, a practice begun on Apollo 14. The LM then began its powered descent with a full load of descent stage fuel. This method allowed the final three Apollo landings to be made with enough reserve fuel for over a minute of hover time.

Specifications

Note that weights varied from mission to mission; those given here are an average for the non-ELM class vehicles. See the individual mission articles for each LM's weight.

Ascent stage

The Ascent stage contained the crew cabin; environmental control (life support) system; instrument panels; overhead hatch/docking port; forward EVA hatch; sixteen Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters (identical to those used on the Service Module) mounted in four quads; rendezvous radar; VHF and S-band communications equipment and antennas; guidance and navigation systems (primary and backup); active thermal control system (an ice sublimator); Ascent Propulsion System (APS) engine; and enough fuel, battery power, cooling water, and breathing oxygen to return to lunar orbit and rendezvous with the Apollo Command/Service Module. The ascent stage also carried lunar rock and soil samples back with the crew, as much as 238 pounds (108 kg) on Apollo 17.

- Crew: 2

- Crew cabin volume: 235 cubic feet (6.7 m3)

- Height: 9.29 feet (2.83 m)

- Width: 14.08 feet (4.29 m)

- Depth: 13.25 feet (4.04 m)

- Mass including fuel: 10,300 pounds (4,700 kg)

- Atmosphere: 100% oxygen at 4.8 pounds per square inch (33 kPa)

- Water: two 42.5-pound (19.3 kg) storage tanks

- Coolant: 25 pounds (11 kg) of ethylene glycol/water solution

- Thermal Control: one active water-ice sublimator

- RCS propellant mass: 633 pounds (287 kg)

- RCS thrusters: sixteen x 100 pounds-force (440 N) in four quads

- RCS propellants: Aerozine 50 fuel / nitrogen tetroxide(N2O4) oxidizer

- RCS specific impulse: 290 sec (2,840 N-sec/kg)

- APS propellant mass: 5,187 pounds (2,353 kg)

- APS engine: Rocketdyne RS-18 [10]

- APS thrust: 3,500 pounds-force (16,000 N)

- APS propellants: Aerozine 50 fuel / nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer

- APS pressurant: two 6.4-pound (2.9 kg) helium tanks at 3,000 pounds per square inch (21 MPa)

- APS specific impulse: 311 sec (3,050 N-sec/kg)

- APS delta-V: 7,280 feet per second (2,220 m/s)

- Thrust-to-weight ratio at liftoff: 2.124 (in lunar gravity)

- Batteries: two 28–32 volt, 296 ampere-hour silver-zinc batteries; 125 pounds (57 kg) each

- Power: 28 V DC, 115 V 400 Hz AC

Descent stage

The Descent stage contained the landing gear; EVA ladder; landing radar; Descent Propulsion System (DPS) engine and fuel to land on the Moon. It had several cargo compartments with replacement Portable Life Support System (PLSS) batteries and lithium hydroxide canisters; the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package ALSEP; Mobile Equipment Cart (a hand-pulled equipment cart used on Apollo 14) or the Lunar Rover (used on Apollo 15-17); deployable S-band antenna (Apollo 11-14); surface television camera; surface tools; and lunar sample collection boxes. The descent stage carried consumables for the lunar stay: batteries; oxygen and water for drinking and cooling. The No. 1 landing gear leg carried an aluminum plaque near the ladder commemorating each landing flight, listing the names of the astronauts, and in the case of the first and last, the President of the United States (Richard M. Nixon).

- Height minus landing probes: 8.59 feet (2.62 m)

- Width/depth minus landing gear: 12.83 feet (3.91 m)

- Width/depth incl. landing gear: 31.0 feet (9.4 m)

- Mass including fuel: 22,783 pounds (10,334 kg)

- Water: one 151-kilogram (330 lb) storage tank

- DPS propellant mass: 18,000 pounds (8,200 kg)

- DPS thrust: 10,125 pounds-force (45,040 N), throttleable between 10% and 60% of full thrust

- DPS propellants: Aerozine 50/nitrogen tetroxide

- DPS pressurant: one 49-pound (22 kg) supercritical helium tank at 1,555 pounds per square inch (10.72 MPa)

- DPS specific impulse: 311 sec (3,050 N-sec/kg)

- DPS delta-V: 8,100 feet per second (2,500 m/s)

- Batteries: four (Apollo 9-14) or five (Apollo 15-17) 28–32 V, 415 A·h silver-zinc batteries; 135 pounds (61 kg) each

Lunar Modules produced

| Serial number | Name | Use | Launch date | Current location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM-1 |

Apollo 5 | January 22, 1968 | Reentered Earth's atmosphere |  |

|

| LM-2 |

Intended for second unmanned flight; not used |

On display at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, DC | |||

| LM-3 | Spider | Apollo 9 | March 3, 1969 | Reentered Earth's atmosphere |  |

| LM-4 | Snoopy | Apollo 10 | May 18, 1969 | Descent stage impacted Moon; Ascent stage in solar orbit (the only surviving flown LM ascent stage) |  |

| LM-5 |

Eagle | Apollo 11 | July 16, 1969 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage left in lunar orbit, eventually crashed on Moon |  |

| LM-6 | Intrepid | Apollo 12 | November 14, 1969 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage deliberately crashed into Moon |  |

| LM-7 | Aquarius | Apollo 13 | April 11, 1970 | Reentered Earth's atmosphere |  |

| LM-8 | Antares | Apollo 14 | January 31, 1971 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage deliberately crashed into Moon |  |

| LM-9 | Not flown (originally intended as Apollo 15, last H-class mission) |

On display at the Kennedy Space Center (Apollo/Saturn V Center) |

|

||

| LM-10 | Falcon | Apollo 15, first ELM | July 26, 1971 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage deliberately crashed into Moon |  |

| LM-11 | Orion | Apollo 16 | April 16, 1972 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage left in lunar orbit, eventually crashed on Moon |  |

| LM-12 | Challenger | Apollo 17 | December 7, 1972 | Descent stage on lunar surface; Ascent stage deliberately crashed into Moon |  |

| LM-13 |

Not flown (originally intended as Apollo 19) |

Partially completed by Grumman; restored and on display at Cradle of Aviation Museum, Long Island, New York. Also used during HBO's 1998 mini-series From the Earth to the Moon. | |||

| LM-14 |

Not flown (originally intended as Apollo 20) |

Never completed; unconfirmed reports claim that some parts (in addition to parts from test vehicle LTA-3) are included in LM on display at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia (see Franklin Institute web page.) | |||

| LM-15 |

Not flown (might have been Apollo Telescope Mount) |

Scrapped |

|||

| * For the location of LMs left on the Lunar surface, see the list of artificial objects on the Moon. | |||||

Proposed derivatives

Apollo Telescope Mount

One proposed Apollo Application was an orbital solar telescope constructed from a surplus LM with its descent engine replaced with a telescope controlled from the ascent stage cabin, the landing legs removed and four "windmill" solar panels extending from the descent stage quadrants. This would have been launched on an unmanned Saturn 1B, and docked with a manned Command/Service Module, named the Apollo Telescope Mission (ATM).

This idea was later transferred to the original wet workshop design for the Skylab orbital workshop and renamed the Apollo Telescope Mount to be docked on a side port of the workshop's Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA). When Skylab changed to a "dry workshop" design pre-fabricated on the ground and launched on a Saturn V, the telescope was mounted on a hinged arm and controlled from inside the MDA. Only the octagonal shape of the telescope container, solar panels and the Apollo Telescope Mount name were kept, though there was no longer any association with the LM.

LM truck (aka Lunar Payload Module)

The Apollo LM Truck was a stand-alone LM descent stage intended to deliver up to 11,000 pounds (5.0 t) of payload to the Moon for an unmanned landing. This technique was intended to deliver equipment and supplies to a permanent manned lunar base. As originally proposed, it would be launched on a Saturn V with a full Apollo crew to accompany it to lunar orbit and then guide it to a landing next to the base; the base crew would then unload the "truck" while the orbiting crew returned to earth.[11] In later AAP plans, the LPM would be delivered by an unmanned lunar ferry vehicle.

Depiction in fiction

The development and construction of the lunar module is dramatized in the miniseries From the Earth to the Moon episode entitled "Spider". This is in reference to LM-3, used on Apollo 9, which the crew named Spider after its spidery appearance.

The Ron Howard film Apollo 13, a dramatization of that mission, was filmed using realistic spacecraft interior reconstructions of the Aquarius and the Command Module Odyssey. Actors portrayed the crew, floating realistically during most of the mission in scenes filmed in NASA's zero-g training aircraft.

Media

See also

- Apollo Command/Service Module

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- Lunar rover

- Project Apollo

- Lunar Escape Systems

Notes

- ↑ Moon Race: The History of Apollo DVD, Columbia River Entertainment (Portland, OR, 2007)

- ↑ Apollo 11 Lunar Orbit Phase

- ↑ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co.. p. 194-196. ISBN 0025428209.

- ↑ Father of the Lunar Module Thomas Kelly Dies, Space.Com

- ↑ A similar guidance system was used in the Command Module)

- ↑ "LM Electrical". Encyclopedia Aeronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/lmerical.htm.

- ↑ "LM Landing Gear". Encyclopedia Aeronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/lmlggear.htm.

- ↑ Unconventional, Contrary, and Ugly: The Lunar Landing Research Vehicle Gene J. Matranga, C. Wayne Ottinger, and Calvin R. Jarvis with C. Christian Gelzer Monograph is Aerospace History #35 NASA SP-2004-4535, 2005

- ↑ Courtney G Brooks, James M. Grimwood, Loyd S. Swenson (1979). "Chapter 12 Part 7". Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA. ISBN 0486467562. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch12-7.html. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Apollo LM Truck on Mark Wade's Encyclopedia Astronautica – Description of adapted LM descent stage for the unmanned transport of cargo to a permanent lunar base.

References

- Kelly, Thomas J. (2001). Moon Lander: How We Developed the Apollo Lunar Module (Smithsonian History of Aviation and Spaceflight Series). Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-998-X.

- Baker, David (1981). The History of Manned Space Flight. Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54377-X

- Brooks, Courtney J., Grimwood, James M. and Swenson, Loyd S. Jr (1979) Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft NASA SP-4205.

- Sullivan, Scott P. (2004) Virtual LM: A Pictorial Essay of the Engineering and Construction of the Apollo Lunar Module. Apogee Books. ISBN 1-894959-14-0

- Stoff, Joshua. (2004) Building Moonships: The Grumman Lunar Module. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3586-9

- Stengel, Robert F. (1970). Manual Attitude Control of the Lunar Module, J. Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 7, No. 8, pp. 941-948.

External links

- Google Moon overview of Apollo landing sites

- NASA catalog: Apollo 14 Lunar Module

- Space/Craft Assembly & Test Remembered – A site "dedicated to the men and women that designed, built and tested the Lunar Module at Grumman Aerospace Corporation, Bethpage, New York"

- We Called It 'The Bug', By D.C. Agle, Air & Space Magazine, September 01, 2001 - Excellent overview of LM descent

- Apollo 11 LM Structures handout for LM-5 (PDF) – Training document given to astronauts which illustrates all discrete LM structures

- Apollo Operations Handbook, Lunar Module (LM 10 and Subsequent), Volume One. Subsystems Data (PDF) Manufacturers Handbook covering the systems of the LM.

- Apollo Operations Handbook, Lunar Module (LM 11 and Subsequent), Volume Two. Operational Procedures Manufacturers Handbook covering the procedures used to fly the LM.

- Apollo 15 LM Activation Checklist for LM-10 – Checklist detailing how to prepare the LM for activation and flight during a mission

- Lunar Module Launch Video

- [2] On-line 2D Lunar Module Landing Simulation Game

- Easy Lander 3D Lunar Module Landing Simulation Game

|

||||||||||